Exotropia: A Disability the Camera Loves?

I recently began to notice something, and after you read this you might as well.

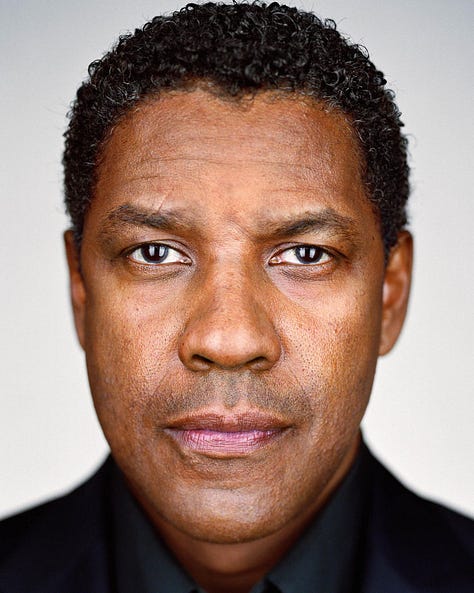

You will probably start to notice that Denzel Washington’s eyes don’t quite point in the same direction. Not all the time, just occasionally. When he’s relaxed, or tired, or doing that dramatic gaze past a face and into a person’s soul. One eye will be locked on target while the other drifts lazily outward, like it’s bored with the conversation or taking cues from off-stage.

And once you see it in Denzel, you’ll see it everywhere. Russell Crowe has it. So does Jason Momoa. Catherine Zeta-Jones. Ryan Gosling. Mila Kunis. Rami Malek. Penélope Cruz. The list keeps growing, and at some point you start to wonder: is this a coincidence, or is there something about having slightly wall-eyed stares that makes you better at being filmed for a living?

The condition is called intermittent exotropia. Exotropia means the eyes point outward (as opposed to esotropia, where they cross inward). Intermittent means it doesn’t always show. Medical literature suggests it affects about 1% of adults. So either I’ve stumbled onto a peculiar coincidence, or something more interesting is going on.

The Engineering Problems with Human Eyes

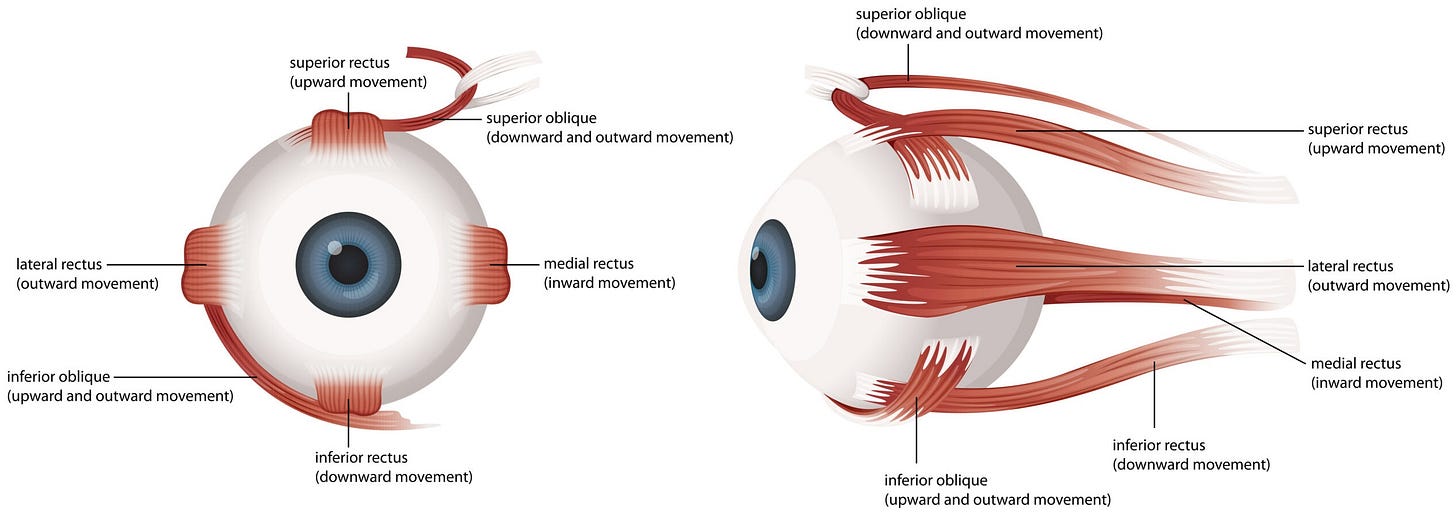

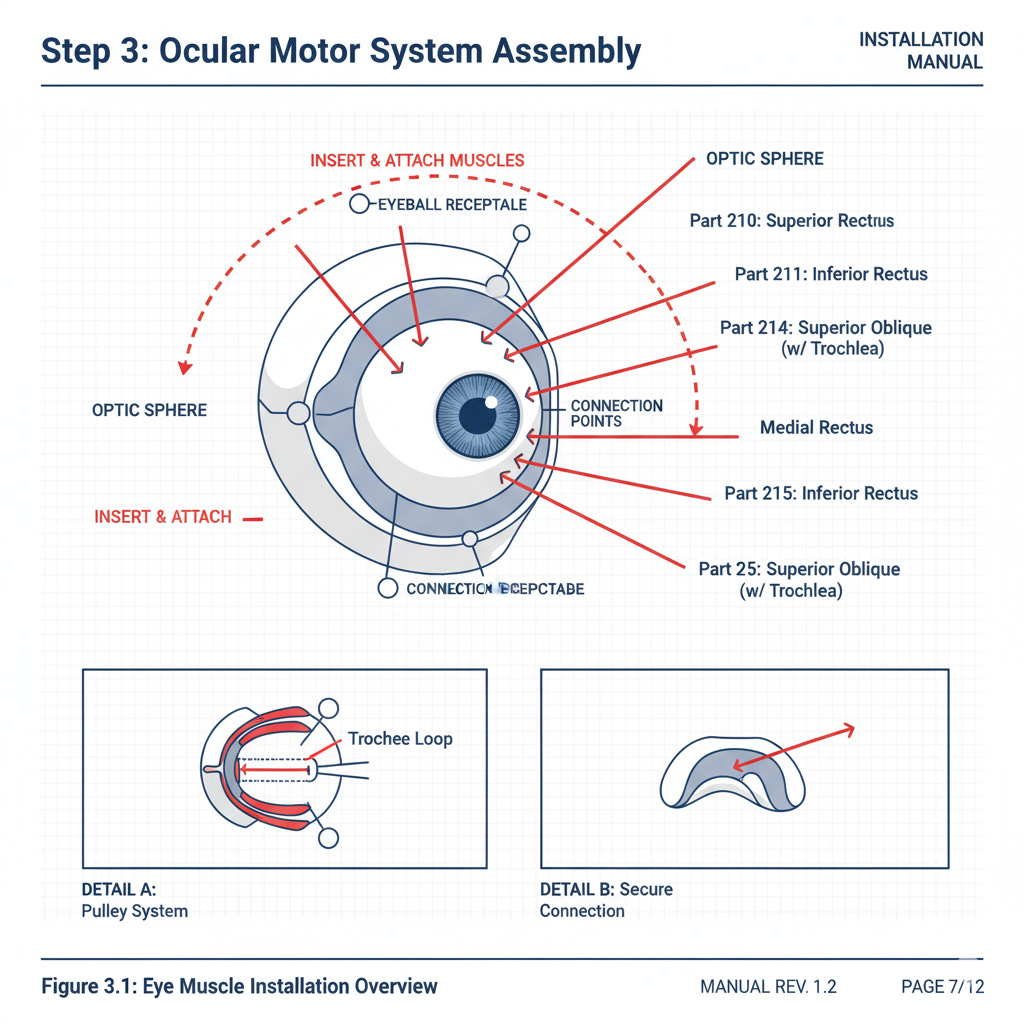

Your eyes are not firmly bolted into your skull like headlights on a car. They’re sitting in sockets, tethered to six muscles each — twelve muscles total, all needing to be coordinated with astonishing precision if you want to do basic tasks like see one image instead of two.

Now imagine an assembly line for human bodies. There’s a station where someone has to drop eyeballs into their sockets and hook up six muscles to each one. And as with any manufacturing process, there’s variance. Sometimes the eyeball goes in at a slightly wrong angle. Sometimes a muscle attaches a millimeter too far forward or back. Sometimes the muscle itself is a bit stretchy or a bit stiff.

For most people, this variance doesn’t matter. Your brain’s fusion system — the physiological circuits that take the slightly different images from each eye and weld them into a single 3D perception — is powerful enough to compensate. It continuously adjusts those twelve muscles to keep your eyes converged on whatever you’re looking at.

But the system has limits. If an eye was “installed” poorly then bringing it into alignment takes constant work. It’s like holding a weight. The weight — measured in prism diopters (PD) — is the difference between the natural position of the eye and how far it has to move to get to alignment. Your fusional convergence is the strength you have available to hold that weight. If the weight is 15 PD and you can only muster 10 PD of strength, your fusion system fails. One eye drifts off-target. You get double vision, or your brain suppresses one image entirely.

The clinical guideline is called Sheard’s Criterion: strength should be at least twice the weight. This provides a comfortable safety margin. If you’re at the edge — if you can barely pull your eyes into convergence — you’re probably straining constantly, getting headaches, and your eye will visibly wander when you’re tired or distracted.

The Diagnostic Problem

Here’s where my original question gets tricky.

I wanted to do a proper study: Take headshots of top-billed actors, measure the degree of eye divergence, compare it to a control group of people. Simple epidemiology. But the more I dug into the medical literature, the more I realized this is way more complex than that.

First problem: intermittent exotropia is intermittent.

It might require more eye muscle, but most of these actors can converge their eyes just fine when they want to. So we would be looking for the moments when they let go — when they’re relaxed, distracted, exhausted, or just gazing into space between takes. You could watch someone for hours and never catch it.

This creates a diagnostic asymmetry: if you ever see someone’s eyes diverge, even for a moment, they probably have at least mild intermittent exotropia. But if you don’t see it, that proves nothing. They might have it and just keep it tightly controlled when being observed.

For popular actors we have thousands of hours of video and countless paparazzi photos. We’re playing the odds across a massive sample size. For random people? Unless you follow them around with a camera crew or send them to an ophthalmologist for a clinical exam, you’ll miss most cases.

So maybe exotropia is more common in actors. Or maybe it’s equally common in everyone, and we just don’t notice it in people who don’t work in front of the camera.

Second problem: many people can voluntarily diverge their eyes.

This one surprised me. I had reasoned that since the human visual system is built around binocular fusion there would be no benefit in being able to push your eyes out of vergence (which creates two images that your brain can’t fuse). Benefit or no, it turns out that many people can push their eyes outwards, mimicking the walleye signature of real exotropia. Which means a single photograph might capture a voluntary, transient divergence that has nothing to do with exotropia. False positive.

Third problem: pseudoexotropia.

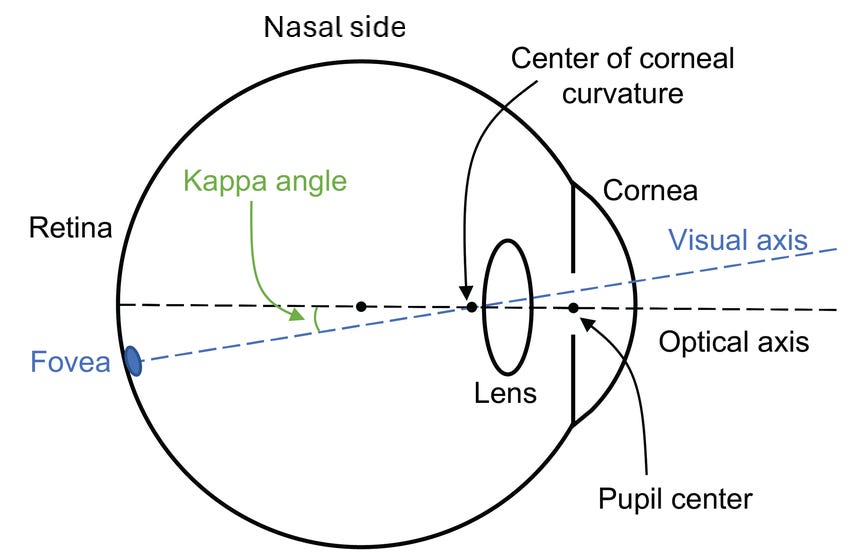

Your fovea — the small spot on your retina that produces high-resolution vision — isn’t exactly centered behind your pupil. The offset can be measured, and is referred to in the literature as Angle Kappa. For most people Angle Kappa is positive, meaning the fovea is offset slightly toward the temple side of each eye.

The median Angle Kappa in adults is around +3 degrees, with 95% of people falling between 0 and +6 degrees. At the extreme end of the distribution, with Angle Kappa above +5 degrees, this difference in alignment creates pseudoexotropia: the eyes appear to be diverging even when they’re producing normal binocular fusion.

An ophthalmologist can distinguish this from true exotropia with a cover test. In pseudoexotropia, covering one eye doesn’t cause the other eye to move, because it was already aimed correctly. In true exotropia, uncovering the eye triggers a corrective movement inward.

But in a photograph? No way to tell.

The Difficult Question

So here’s where I am: I have a list of very famous, photogenic people who appear to have intermittent exotropia. I have a condition that supposedly affects around 1% of adults. And I have three confounding variables that make it nearly impossible to confirm the presence of the condition outside of a clinic.

Can intermittent exotropia actually make a person more photogenic? Can it make someone a more appealing screen actor?

Think about what exotropia does. It breaks the usual rules of where eyes should point. When someone with normal eye alignment looks at you, their eyes converge on a single point — your face, the camera lens, whatever. It’s predictable and symmetric.

When someone with intermittent exotropia looks at the camera, there can be a subtle ambiguity. One eye is locked on you; the other is ... where, exactly? It’s not looking away from you, not obviously. It’s just slightly detached. Slightly uncoupled. The person is present but also somewhere else.

In photography, we talk about eyes that “draw you in.” Eyes that are “captivating” or “haunting” or “intense.” Could it be that a touch of exotropia creates visual interest? That it makes the viewer work harder to figure out what the person is looking at, and that extra cognitive effort translates into engagement?

Or maybe I’m a victim of the frequency illusion: I noticed it in a few famous people, started looking for it, and now I see it everywhere.

The Thing I Can’t Unsee

Look at that Martin Schoeller portrait of Denzel Washington. It has Schoeller’s signature style: subject captured with a relaxed but direct gaze, flooded with flash lighting that reveals the finest details. Denzel’s eyes are slightly divergent in that photo. Not dramatically. He’s compensating, holding them mostly straight, but not completely. The divergence is there.

Now go watch Training Day or Malcolm X or literally any Denzel movie. Wait for the moments when he’s distracted. Watch his eyes. You’ll see it.

And once you see it, you’ll start to see it everywhere. You’ll notice Mila Kunis’s left eye in Black Swan. Jason Momoa’s gaze in Aquaman. The slight wall-eyed quality to Russell Crowe’s intense stares. That thing with Ryan Gosling’s eyes that you couldn’t quite pinpoint but always found captivating.

Do movie stars have a higher rate of intermittent exotropia than the general population? I went down a rabbit hole of ophthalmology papers and anatomy, prism diopters and angles, strabismus and dark vergence. I collected photographs to scrutinize and compare eyes.

And my answer is: I don’t know. The measurement problem is too hard. The confounders are too numerous. In fact, the prevalence of the condition across the population might be higher than reported because most people with intermittent exotropia may not get diagnosed: eye strain is just part of their lives, and nobody is studying their eye alignment that closely.

But my suspicion is that there’s something about a slight, intermittent misalignment of the eyes that can read as interesting to the parts of our brains devoted to interpreting facial expressions. Perhaps it creates a little bit of cognitive friction, a tiny mystery that draws our attention as our brain tries to figure out where exactly the person is looking. In the cold calculus of Hollywood casting, where tiny advantages can make the difference between stardom and obscurity, having eyes that can add some ambiguity might actually be an edge.

The camera might actually love it.

In this comment I will document actors who I noticed have strabismus (apparently), and where I noticed it.

* Katee Sackhoff – Fight or Flight

* Taylor Kitsch – The Terminal List: Dark Wolf

I think Dennis Quaid is an example of mild pseudoexotropia.

Very interesting!